Almost every musician navigates unseen barriers in their life and career. In order to shine a light on these issues, Output presents UnMute, a series of online conversations that cover hard-hitting, often undiscussed topics in the music industry. For our first episode, the focal point is race in music. Over the past year, movements like Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate have made the music industry confront its own issues with race, from the lack of diversity in lineups to disparities in royalty payments and more.

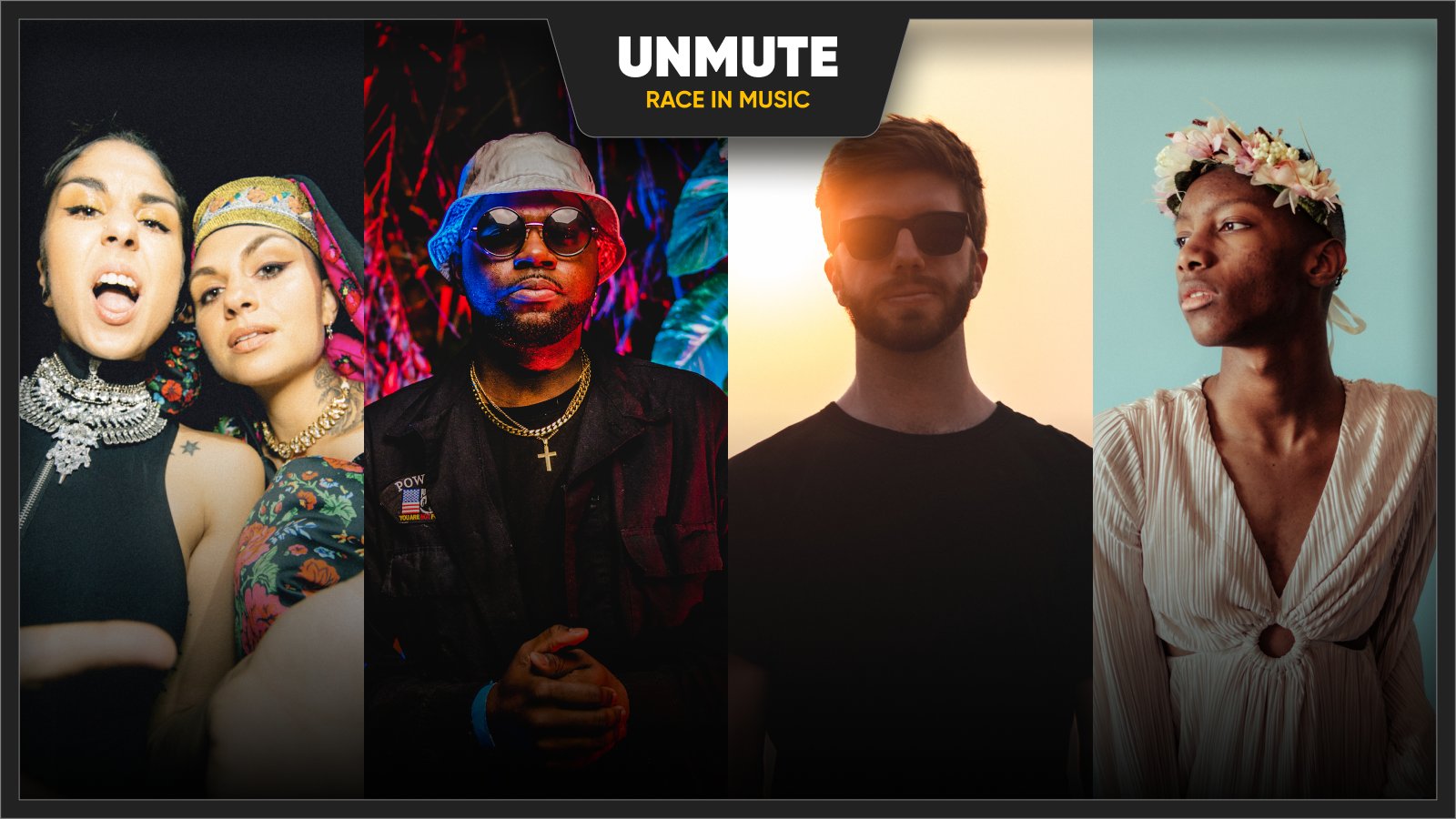

We invited electronic artists Krewella (sisters Jahan and Yasmine), Moore Kismet, Spencer Brown, and G-Buck to the (virtual) table to talk about their personal experiences and what changes the music industry can make as live events come back. Watch the conversation in full or read excerpts from it below. And, make sure to follow Output on Twitch to watch further episodes of UnMute.

Output: Let’s start with a couple of numbers that you may not be surprised by. 73.6% of all musicians, singers, and related workers are white. 13% identify as Black, which leaves only 14% for all other races and ethnicities. A lot of you are in the electronic field and [the] bread and butter is in touring and playing festivals. Looking at bookings for all festivals globally, 77% of all performing acts are white.

Why did you feel it was important to be here and talk about the topic of race?

Moore Kismet: I’ll go ahead and kick this off because the experiences I’ve had have been mixed with ageism and homophobia as well. Every time I see a new lineup getting announced, I always see the same names on those lineups. The vast majority of those names are cis white men who I don’t even know have an inkling of transness or gayness in them. As a result, they are unknowingly further contributing to this broader stereotype of what most people automatically assume electronic music is, which is just a bunch of straight white dudes DJing house music and people senselessly dancing to it for hours. It really bothers me that the perception of how most music is looked at now has shifted to this narrative of strictly white when it used to be everything.

I was viewed as a liability before I blew up. Now everybody who didn’t want to book me before because I was a trans person, because I was black, because of whatever young age I was, now all of a sudden they want me. All of a sudden they want to send me a bunch of booking offers that I don’t think I’ll personally be able to handle during my last year of high school.

“I was viewed as a liability before I blew up.”

MOORE KISMET

I’m just trying to deal with it as best as I can while also making sure that people know that I’m not the only trans person in the electronic music sphere. I’m not the only gay person in the electronic music sphere. I’m definitely not the only black person in the electronic music sphere.

These lineups are still great. They’re still awesome. They’re also great performers, but we need more people representative of diverse communities, of beautiful cultures that deserve to be shared in electronic music that people are actually doing, but aren’t getting enough love for. There should be more of us on these lineups. There should be more women on lineups. There should be more people in the LGBTQ community on these lineups. There should be more people of color or people of other marginalized communities on these lineups.

Do any of you feel like when you are included that it’s tokenized?

Krewella (Yasmine): It’s hard to say because as women, sometimes at the beginning of our career, I just felt lucky to be on a lineup, which I know is not the right mindset to have at all. When you’re starting out, you don’t know if you’re getting chosen because you’re the hot new shit or you’re something to check a box. It still messes with me and I still don’t know how to feel about it a decade later.

“When you’re starting out, you don’t know if you’re getting chosen because you’re the hot new $#it or you’re something to check a box.”

KREWELLA (YASMINE)

Moore Kismet: I totally feel you on that because that’s the kind of period that I’m in right now with everything going on. Obviously I know that some of the stuff where I’m getting booked with my friends is not tokenized. I trust those shows, but it’s shows where the vast majority of the people in the lineup are cis white guys that I’m like, “Hm, I think I’m the only trans person on this lineup.” That’s my immediate thought process. And it sucks.

G-Buck: I’ve been on lineups where I go to my green room and security thinks I’m a rapper. They’re like, “Oh, who are you performing with?” It’s kinda awkward, but that’s just how rare [Black dance artists are booked].

There are so many Jersey club producers from and in New Jersey and the Philadelphia area that don’t even get to smell a big stage. Then we have [big] artists that copy the sound and put it in their music. But it’s these people from the inner cities that don’t even get an opportunity to get an agent.

What can the music industry do better?

Moore Kismet: Talent buyers should try to find a way to look into other artists that aren’t the ones they would typically book. SoundCloud exists, Spotify, Apple Music, Google exists. Search names that you see lots of people talking about in the moment… If it’s a name that you recognize that is within a marginalized community, skip over it if you’ve already booked them. It’s okay. There are plenty of other fish in the sea that you can plug out for your lineups.

I think that if more talent buyers and agencies and promoters really put a focus on looking for talent like me, like G-Buck, like Spencer Brown, like Krewella, they would be taking better strides towards creating a more inclusive environment for electronic music.

G-Buck: Last year when we were shut down and dealing with the George Floyd stuff, we saw the whole industry back Black people and now we’re right back to [how it was]. I don’t know if it’s because promoters have back pay on the artists that they booked from 2019 or 2020.

Krewella (Yasmine): Definitely, same shit different year. There should be an occupation at an agency for someone who’s scraping the internet to find the newest, awesome, cool shit from people from marginalized communities. I don’t know if people are trying to spend money on that. Yet that would only make their company better in every single way. It would make the shows better. It would make everything better.

Moore Kismet: At what point are [companies] going to realize that these people also need to be given a larger platform to spread their music and spread their influence within marginalized communities to show other Black kids like me, other Black adults like Greg, and other queer people that they are not alone in this and you can push to do whatever the fuck you want to do? You don’t get much of that message if off the bat 70% to 80% of the lineup is straight white dudes who don’t know that they’re perpetuating a stereotype.

How does race play into the industry in which you make a living in general?

Krewella (Jahan): I think there’s a safety element here for anyone who’s a person of color or a woman, or however they identify in a marginalized community. Feeling safe is not something that always has to do with your physical safety. It can be just a mindset, even if you will not be harmed physically. It could feel like you’re threatened. It could feel like you’re vulnerable. We’ve been really lucky to literally always do everything together. We’re not traveling solo. We always have each other. We’re very grateful for that. I always say if I was a solo act, I would be in a very different position and I would feel a lot more unsafe than I do when I have my other half with me.

I imagine it can be really alienating, especially when you see the clique culture at a lot of these festivals backstage, which is very apparent. It never really affected us because we have each other. From an outside perspective, we never had a seat at that table. Even from the inception. Maybe I’m just not cool enough. These are the thoughts that come across your head. But it’s a lot more layered than just you as a musician or your personality. It’s more of what you look like and how people want to accept you.

Have you ever been in a situation where you noticed that you might’ve been treated differently because you are perceived as white versus black or brown?

Krewella (Jahan): I think for me personally, more so growing up. And I don’t know how much of it is the story I told myself growing up, feeling like I didn’t fit in whether it was at Islamic school or with Pakistani family gatherings where I felt like I’m the only white girl there and I don’t really fit in and I don’t speak the language, or in school as someone with a foreign name fasting during the month of Ramadan. I think for a lot of mixed-race people, it’s this feeling of no man’s land identity, a lot of ambiguity around not really knowing where you belong. I think as we’ve gotten older we’ve really synthesized all aspects of our multicultural upbringing. For me personally I feel very at home in my mixed-ness.

When we started embracing our ethnic heritage more, which probably started in 2015, people had already known us for four years and we hadn’t really done a lot of that. I’m sure it turned a lot of people off because they’re like, what is this jewelry and these new sounds that I hear in the music and why are we doing this? I don’t want any part of this.

It’s more us now. I do think as a mixed person, it’s super important to own all aspects of ourselves. To remember like we are white, our mother is white and we need to own that part of us too, in the way where there might be an inherent mindset that we’re not aware of as we’re trying to own our brownness too. We have to open ourselves up to being challenged and critiqued along the way, because we’re a part of the problem in so many unconscious ways as well. We’ll only grow from that.

“Making people proud of who they are is the biggest power you have as an artist.”

MOORE KISMET

Spencer Brown: I’m on the opposite side here. If someone sees me or I’m walking into a green room or at a festival, they assume white privileged male that hasn’t gone through any struggles. They have no idea what I went through my whole life trying to discover my identity. They just assume I’ve had it easy because I’m a white privileged male. They have no idea internally what I’ve gone through. What I’ve gone through with my friends would have gone through with my family what I’ve gone through with the fan base. People assume I have it so easy, but actually you don’t know what’s going on in someone’s brain. Coming to my identity was very difficult.

It was over a decade of self-realization and understanding who I was. I do look like a privileged white male, but there’s a lot under the surface that you don’t even know.

What motivates you to keep pressing on?

G-Buck: The whole reason why I got into dance music is that I grew up in the inner city and it wasn’t really cool to like dance music until Diplo came around with Mad Decent in Philly. I was always the outcast. I always thought it was cool to be myself and still like hip-hop but also explore this dance avenue. There are a lot of people in the hood that just call it techno. I want to bring the worlds together and have these Black kids in Philly be like, damn, G-Buck did that.

It’s also for my family because you have to understand being Black, inner-city, it’s tough to even get to this point where we are now. You can think that you’re not doing much, but we’re here on the Output platform right now talking about it.

“Let’s stop using tragedies and hashtag movements to start calling your minority friends in the industry.”

G-BUCK

Krewella (Jahan): I love how you said a huge motivation for you is knowing that people who look to you and see you as an example will be motivated to not only create the music, but like the music and go to the shows. When Yasmine and I started really embracing our Pakistani heritage and rekindling our relationship with that for the first time in years, it started showing on the outside. I noticed that we were attracting fans who were coming to us even if they weren’t Pakistani or Indian or Bangladeshi. They were like, you guys inspired me to stay in touch with my roots too. Hearing about people wanting to integrate that into themselves and to not lose sight of a big part of their upbringing without the shame… that’s been super inspiring for us.

Growing up I did not tell people I was Pakistani, especially after 9/11. It was unspoken. I would say I was Indian or something else. Now I’m so proud to say that and I don’t really care what people think.

Moore Kismet: Making people proud of who they are is the biggest power you have as an artist.

If each one of you could make one ask of our allies, what would it be?

Moore Kismet: Look into the change that you want to see in the music industry. If you want to see more Black people, if you want to see more LGBTQ people, if you want to see any other person within a marginalized community on lineups, push for that. Ask for your favorite artists within these communities to be on those lineups, because I’m pretty sure that the vast majority of promoters weren’t listening before, but I know for a fucking fact they’re listening now. Take the time to look into who you love as an artist, and push them harder than you ever have before out to the forefront.

Krewella (Jahan): I would ask to put pressure on the people in positions of power, like the A&Rs, the people who are curating the playlists, the artists who are defining our reality of what we imagined dance music to be. Because they have the power to shape people’s tastes. Tastes can be shaped in so many different ways. I would definitely ask that the people at the top start also curating their employees and the decision-makers also be reflective of diverse groups.

“A lot of promoters see bringing on underground or underrepresented talent as a risk.”

KREWELLA

G-Buck: Let’s stop using tragedies and hashtag movements to start calling your minority friends in the industry. That’s how this stuff changes. You can’t wait until there’s a Stop Asian Hate movement and then call every Asian person in your phone that day. Be like that every day for everybody. It has to be a daily project.

Spencer: When I was getting into dance music as a teenager everyone was handing out kandi that said PLUR on it. I think that is the most important thing. Have peace, love one another, you can all come together, and respect one another. It’s really simple. This whole scene has been founded on those principles. I think it’s really important, no matter who you are, no matter your religion or your race or your gender or whatever you believe or your sexuality, respect one another and love one another and come together.

Krewella (Jahan): I want to add one more thing. A lot of promoters see bringing on underground or underrepresented talent as a risk. We need to stop using that narrative and see it as an asset, to not just the festival or their business, but to humanity as a whole.