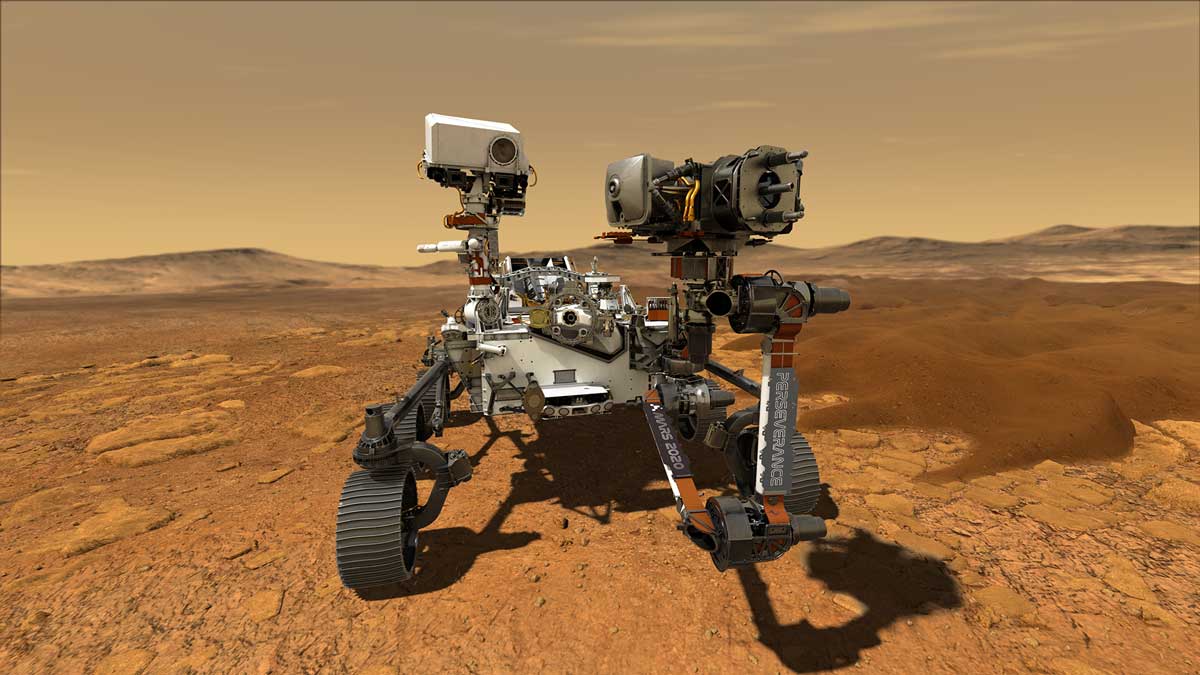

Humans have looked at images of Mars with wonder and awe ever since the Viking 1 lander took the first photograph of the Red Planet back in 1976. But we never knew what it sounded like until this year. Everything changed on February 18th, 2021, when NASA’s Perseverance rover touched down on Mars carrying, among all sorts of scientific contraptions, two microphones. A few days later, the first audio recording of the surface of Mars was publicly released. Full of clanks and wind muffle, the 18-second clip was five years in the making. And, we’re able to listen to it because of one Los Angeles-based rocker named Jason Achilles Mezilis.

Mezilis, who goes by the artist name Jason Achilles, is broad strokes a multi-instrumentalist, producer, and composer. He’s played in several bands over the years, composed full orchestral works, and has his own boutique studio nestled in DTLA called Organic Audio Recorders. Most recently, he worked with Guns n’ Roses keyboard player Dizzy Reed on his solo album.

At first glance, the curly-haired rocker might not fit the archetype of an extraterrestrial audio scientist, but he’s been obsessed with space for as long as he can remember. His dad was a computer systems analyst and a musician. He took astronomy courses in school. He reads science magazines and attends space exploration events and lectures for fun.

Mezelis might spend his days working on Earthly musical matters, but his eyes and his ears are directed at the stars.

The road to Mars

“I’m not the first person to have the idea of capturing the sound on the surface of Mars,” Mezilis admits to Output.

People have been kicking around the idea for over 20 years. Back in 1996, Carl Sagan wrote a letter to NASA urging the agency to put a microphone on its next lander. “Even if only a few minutes of Martian sounds are recorded from this first experiment, the public interest will be high and the opportunity for scientific exploration real,” Sagan wrote.

Since then, microphones have tried to make it to Mars, but without success. The first microphone was sent to Mars in the late ’90s on NASA’s Mars Polar Lander. The lander sadly crashed on the planet’s surface. Then, there was a French Mars mission in the aughts that included a microphone. It was deemed too expensive and canceled. In 2008, NASA’s Mars Phoenix lander safely arrived on the Red Planet with a microphone. But the mic was turned off at the last minute for technical concerns and nothing was ever recorded.

“[NASA’s] attitude is… it would be great if the microphone works, but if it doesn’t, we don’t care as long as it doesn’t break off and hit a $2 billion piece of equipment.”

It had been years since anyone last tried to get a microphone to Mars, and Mezilis wanted to change that. In 2016 over a dinner with Joseph Carsten, a friend who works in NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Mezilis excitedly talked up the idea of putting a microphone onto the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover. His reasoning? “Because it would be fucking cool.”

Carsten didn’t say yes to the idea, but he also didn’t say no. It was all Mezilis needed. So, without formal approval from NASA, he began his research.

A few months into preparing his pitch for NASA, he heard back from Carsten. There was a new development — NASA decided that the Perseverance rover would capture audio and get kitted out with not one, but two microphones.

One microphone would sit in a device called the Supercam to record the sounds of an infrared laser beam vaporizing bits of Martian rock. The second microphone would exclusively capture the audio of the rover’s entry, descent, and landing (EDL), which could be paired with EDL video later on.

Mezilis was determined to be involved and shifted into overdrive to angle in on the less scientific EDL team. He wrote three short white papers that addressed thoughts, concerns, and the different ways he could be an asset to the project. He even hired an audio expert named Caesar Garcia to help him cull together recommendations.

The EDL team got back to him immediately. They liked his ideas. And in 2017, Mezilis and his team were contracted by NASA. He was officially part of the Mars Perseverance rover mission.

Building a Martian microphone

Every bit of equipment added to a thing launched into space has consequences. It takes up physical space, adds weight, requires additional fuel, and introduces more variables for things to go wrong. The rover’s job is to collect samples and it was already packed with everything from a drill to a core-sampling mechanism. So, that NASA chose to include the second microphone when there was no scientific reason for it was a celebration in its own right.

While this second microphone could help NASA design more accurate atmospheric models of Mars or troubleshoot broken equipment on the rover, Mezilis says that ultimately, “It was to create a more compelling video of the landing sequence. It’s mainly for public outreach.” Basically, it’s a bonus feature. NASA didn’t even count on the microphone being usable on Mars. Before the rover launched, NASA said it was “unlikely it will work beyond landing.”

To prepare, Mezilis spent two months drafting a 19-page evaluation study for a custom-built microphone and preamp that could fit inside a one-inch cube. Then, NASA delivered bad news. It couldn’t afford to custom-make anything. He had to hack together store-bought gear instead.

“The whole thing with space is, it has to cost nothing, weigh nothing, pose no risk to any adjoining system, and then you’re clear to hop on board,” says Mezilis. “NASA’s main concern was that the microphone didn’t fuck up anything else. Their attitude is: it would be great if the microphone works, but if it doesn’t, we don’t care as long as it doesn’t break off and hit a $2 billion piece of equipment.”

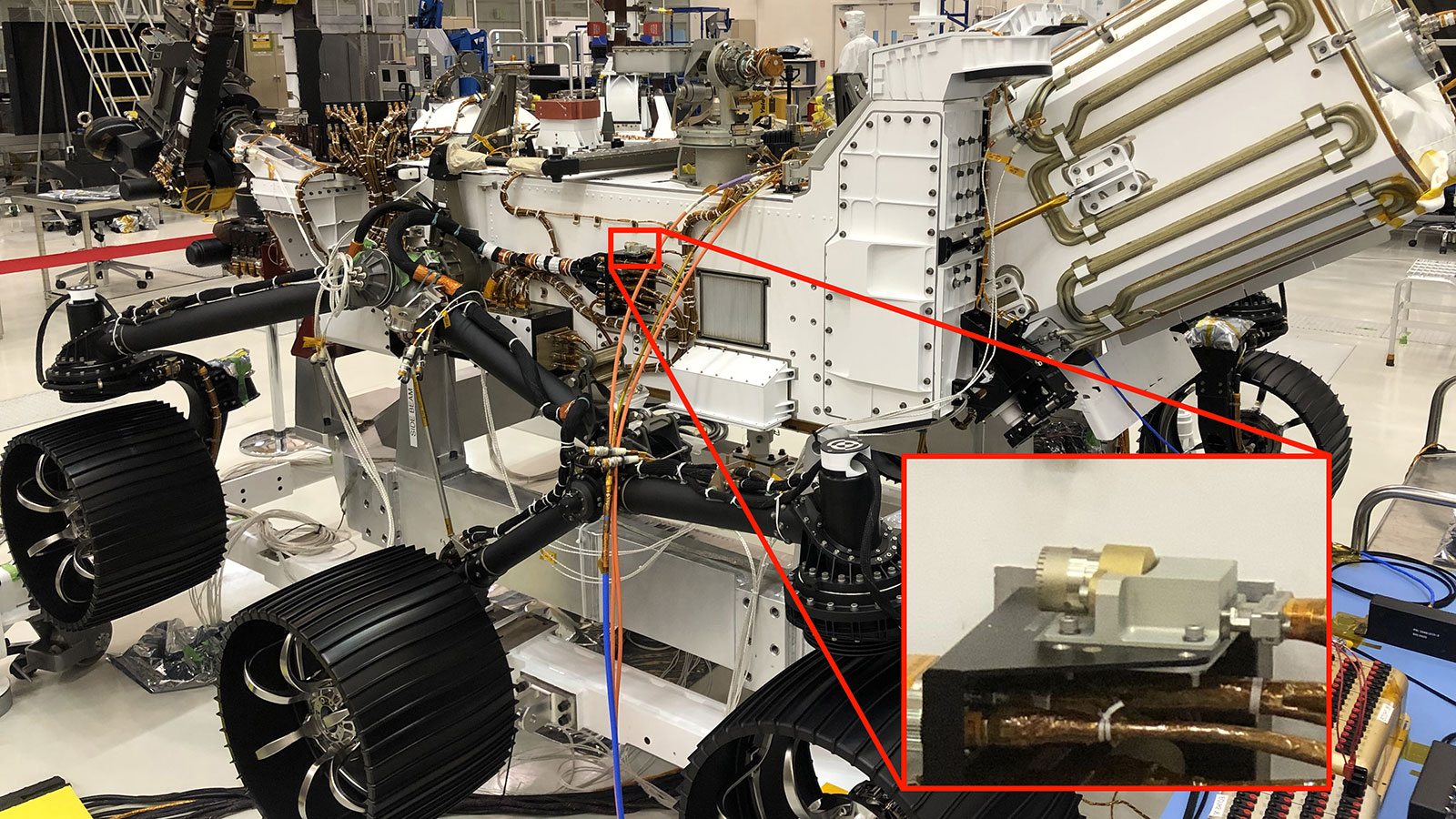

The team decided on a bunch of gear from DPA, a Danish pro audio company that specializes in lavalier microphones. They used the company’s MMC4006 omni pencil microphone capsule, MMA-A digital audio interface, and MMP-G modular active cable. The digital audio interface is what ultimately tipped the scales in DPA’s favor. It’s tiny, clocking in at about two inches in diameter, and weighs a negligible half an ounce.

Here’s how it all works. First, the mic picks up sound as an analog signal. Then, the cable acts as a preamp, boosting sound to feed it into the audio interface. Last, the audio interface digitizes the signal and sends it to a computer in the rover through a USB connection. Once the rover has a recording, it delivers the audio to Earth through software that NASA built. There’s a 3 to 22-minute delay in each direction, which isn’t bad when you consider the file has to travel 201.6 million miles.

Surprisingly, there are few modifications to the system. There’s a wafer-thin dust screen installed on the inside of the microphone to keep the diaphragm clean. And, the computer board from the audio interface is in a new, smaller housing inside the rover chassis. The microphone itself is covered by a custom brass mounting bracket located outside the rover above the middle wheel on the left side. That’s it.

If you wanted to buy the setup yourself, the three pieces cost about $3,000 and can fit in the palm of your hand.

Planning for the unknown

“There are a lot of engineers at NASA who can read charts, understand tolerances and figure out vibration sensitivities,” says Mezilis. “My goal was making sure it sounded good. We needed a real high dynamic range and good frequency response.”

DPA’s MMC4006 mic fits all the specs needed. Not only is it minuscule — about a half-inch wide — it has a pretty flat frequency response and picks up audio from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. “The dynamic range was important because we were supposed to capture the audio on the landing, which would be really loud,” says Mezilis. “But then, on the surface, because the atmosphere is so thin, the sound is going to fall off fast. If we were going to try and hear anything outside of the immediate vicinity of the rover, we needed it to be as sensitive as possible.”

Given that sound waves travel in the air through particles that vibrate and collide with other particles, many are surprised to learn that any sound can be heard on Mars. The atmospheric pressure on Mars is less than one percent of Earth’s sea level pressure. Because there are way, way fewer particles to travel through in such a thin atmosphere, sounds are much quieter on Mars than on Earth. To make up for this, Mezilis planned to bump up the microphone’s input by 30 dB once it landed on Mars.

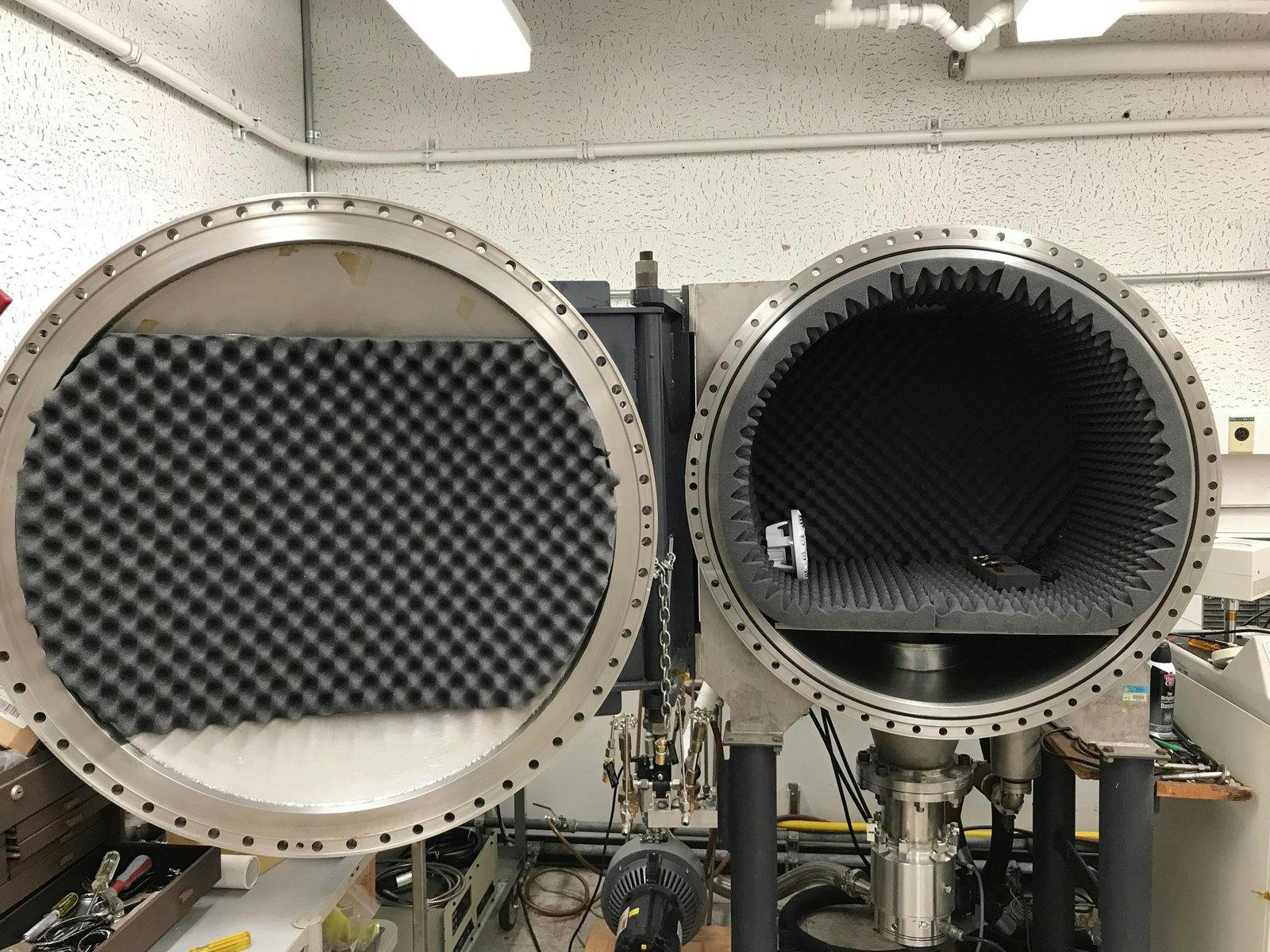

The audio was Mezilis’ primary focus, but there were countless other physical and atmospheric differences that could break the microphone before it even reached the surface of Mars. And, Mezilis had no way to test most of these scenarios before the mission. Concerns included outgassing (which is evaporation in a vacuum), radiation, the huge temperature swings from day to night on Mars, excessive dust on the planet’s surface, gravitational forces, plus the shattering vibrations during the rover’s launch and landing. This mic wasn’t built for any of these situations.

Because of all the aforementioned problems, audio fidelity was not a high priority for NASA. Durability was. The microphone had to hold up in every imaginable scenario. Most space research is done in a theoretical vacuum, but this mic went into a literal vacuum chamber built to mimic the environmental conditions on Mars.

Mezilis draws an analogy: “It’s like if you left your baby in the middle of Death Valley. What would you have to worry about? Well, everything. And probably some shit you didn’t consider before.”

There was a lot of pressure to get things right and no second chance.

A moment of truth

On February 18th, 2021, the Perseverance rover landed on Mars’ surface. And for a brief moment, the accomplishment was both exhilarating and heartbreaking. While the rover itself successfully touched down, no audio was captured from the landing sequence due to a technical issue. For Mezilis, this felt like “five years of work down the drain.”

But, once Perseverance was on Mars’ surface, the EDL microphone was reactivated and came back online. It captured a minute of audio, and 18 seconds from the recording was presented during a NASA press conference on February 22nd. Together, the world listened to Mars for the first time. In the tiny clip, the Red Planet’s wind sounds strangely human and familiar, like an intermittent heartbeat.

Since that first day, the rover’s microphones have been recording all sorts of activities. And on March 17th, NASA released a 16-minute audio file captured by the EDL microphone of the rover driving through Mars’ Jezero Crater. The raw audio is high-pitched and screechy with an uninterrupted hum that is not unlike that of a dial tone of a landline telephone. Then the unmistakable sounds of the rover’s wheels on Mars’ rocky terrain begin.

The dial tone goes up and down in volume while the rover clangs and clunks along. You can also hear sounds from the heat rejection fluid pump, the reverberant space of each item, and the ever-present Martian wind. It’s, for lack of a better term, otherworldly.

“The sounds themselves were unexpected,” says Mezilis. “But the audio quality is what I anticipated based on our studies. Everything we’re hearing on the rover is right next to us. There’s not much attenuation happening in such a short distance and it gets muffled over time.”

Processing the Red Planet

Once the 16-minute recording was publicly available, Mezilis and his engineer Mike Houge downloaded the file from NASA’s SoundCloud and processed it nine times to “remove extraneous noise and amplify the audio properties most true to the environment.” They worked at warp speed to release their interference-free version before anyone else.

“The audio we received from NASA is 48k 16bit stereo WAV,” says Houge. “Although it’s a stereo file, the L and R are identical [since it was recorded with a mono microphone] so it is safe to discard one side. Though you can be sure I checked to make sure both sides were the same.” Then they loaded the file into a Pro Tools session with multiple tracks to audition different processing settings.

To get rid of as much extra noise as possible, the bulk of the editing was done with iZotope RX 8, an audio repair application used to polish up sounds for film, video games, podcasts, and more. Modules in RX 8 like Spectral De-noise “reduced the sound of some of the mechanical bumps and capsule distortions.”

The pair describes the rest of the process with a knowing casualness. They threw on a high-pass filter to shave off dulled low-end frequencies, puttered around with final settings, rendered the processed files, and then exported.

When you listen to the final result, Mezilis and Houge hope you hear “the true sound of the surface.”

NASA’s unaltered file is muffled, with a soft but persistent tinnitus-like ring that sits underneath. In Mezilis and Houge’s cleaned-up version, every clang, squeak, and metallic drag from the rover’s explorations is crystal clear.

Some of the extra noise in the original file is from the microphone picking up its own physical reverberations. “Because our microphone is so tightly bolted to the rover, a lot of sound travels through the body of it,” Mezilis explains.

Other unwanted parts of the recording are due to the type of microphone used. Omnidirectional microphones capture sounds with equal gain from all directions, and register less wind noise and plosives because of how they’re built. But, “It’s hearing everything,” says Mezilis. “That’s not how humans hear. In order to create a realistic audio experience, you have to filter out the background a little bit.”

“My goal in processing these sounds was to create the most realistic listening experience to the environment and the physicality of what we’re trying to hear,” says Mezilis. “It’s like color correction. You take a picture and it doesn’t look anything like what you see. You have to process it to get a true representation of what you’re seeing. We’re not tweaking it. We’re getting it back to where it’s supposed to be. We didn’t equalize anything. All we did was a very delicate noise reduction.”

The next mission

Mezilis’ own music is separate from his aerospace experiences. He has an EP on the way, DISCØ, already preceded by the singles, “RTL (Ready to Launch)” and “Eurotrash.”

As for using the audio captured on Mars in his compositions? “The first day the audio came out I did a quick analysis and realized the drone of that pump was like a microtone flat of G,” he says. “I recorded a strain of it on my piano to the theme of 2001 in the key of G and used it as a drone tone underneath. I’ll let other people write to it. I’ll just play along with it.” (If you want to play around with Mars audio for yourself, it’s available to download on NASA’s website.)

Mezilis’ microphone is still exploring Mars’ surface, capturing audio indefinitely, or until it stops working. Both NASA and DPA provide updates on its activities, and as of now, it’s still operational. Whether more audio will be captured and released for public consumption remains to be seen, or heard, as the case may be.

Meanwhile, Mezilis is working on his proposals for the next mission with the goal of capturing audio in stereo and syncing it up to video. Says Mezilis, “Someday I’d like to sit with my kid and point up and say, ‘I worked on that dot.’”

Words: Lily Moayeri